Resurgam HEMA

powered by TidyHQThe Sources

The Sources

The sources we study for Armizare include both Italian and German sources. It is important to note that while Fiore's writings were penned in Italian and Latin, he himself learned from German masters in the Holy Roman Empire. In addition, German documents of varying quality exist that illustrate the same system of fighting that Fiore teaches - so the oft-used term "Italian Longsword" may be misleading when talking specifically about Fiore's fighting system. Below are listed the explicit documents we use:

- The Flower of Battle

- Fior di Battaglia, "The Getty" - MS Ludwig XV 13

- Flos Duellatorum, "The Novati" - Pisani Dossi MS

- Fior di Battaglia, "The Morgan" - MS M.383

- Florius de Arte Luctandi, "The Paris" - MS Latin 11269

- On the Art of Swordsmanship

- De Arte Gladiatoria Dimicandi, by Philippo di Vadi - MS Vitt. Em. 1324

- Die Blume des Kampfes

- Codex 5278

- The Eyb Kriegsbuch, by Ludwig VI von Eyb - MS B.26

- Codex 10799

The Flower of Battle

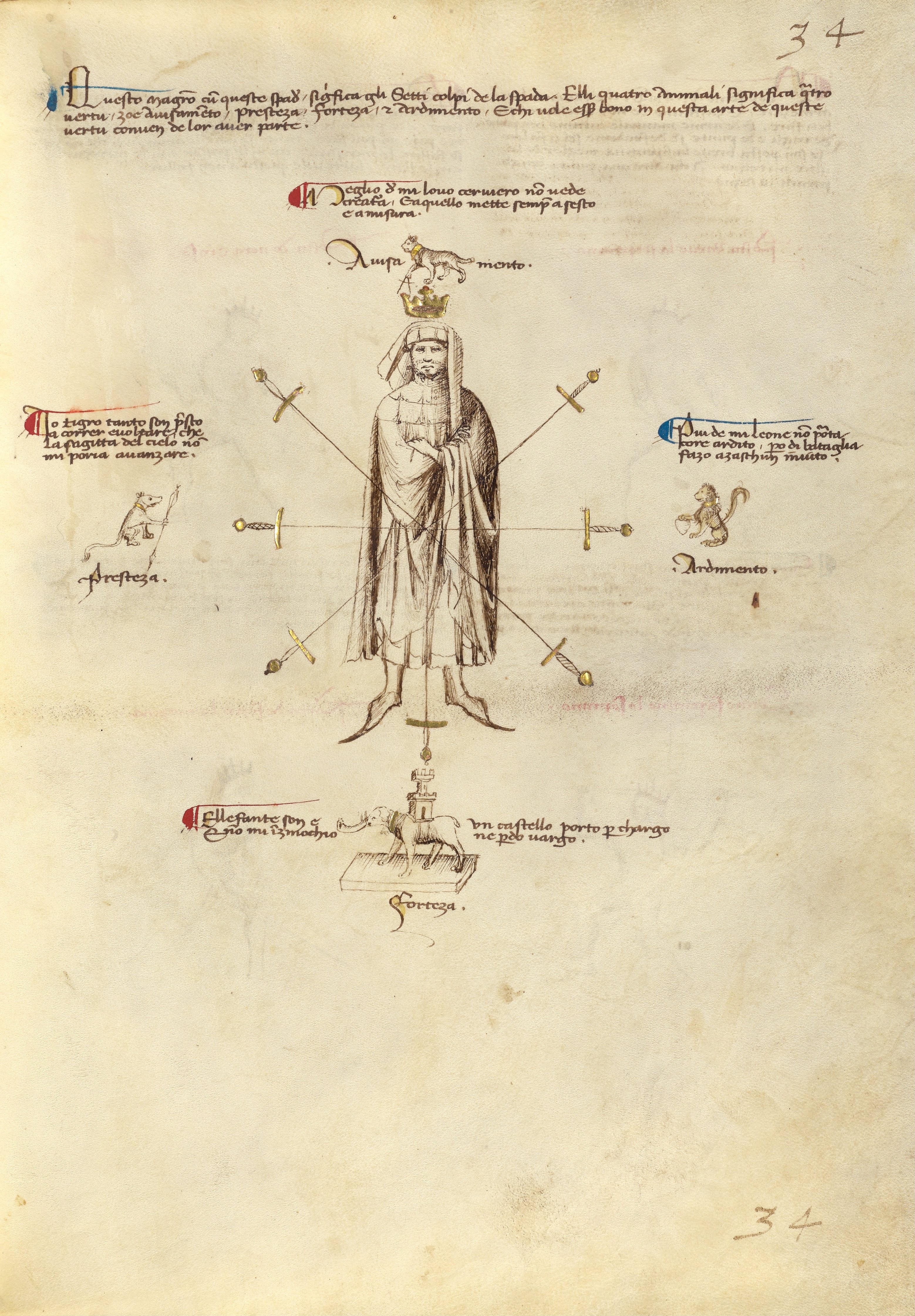

The Flower of Battle refers to the body of surviving manuscripts attributed to Fiore de'i Liberi. While we have four copies of his work, they all differ slightly in what sections they show, how they are illustrated, and how much detail is put into the text. While the drawings may appear crude when compared to later Renaissance artwork, the illustrations in The Flower of Battle are detailed enough to deliver a great deal of information - and it is the distinct combination of descriptive text and images that makes Fiore's manuscripts a robust source to study.

On the Art of Swordsmanship

De Arte Gladiatoria Dimicandi is a fencing treatise written between 1482-1487 by Philippo di Vadi, a 15th century Italian fencing master. Given his possible connections to the d'Este family (the same family to whom Fiore's Getty and Novati MS's are dedicated) it is likely that Vadi had access to Fiore's earlier work which makes sense given the similarites in techniques and organization between Fiore's work and Vadi's. Apart from just the techniques and illustrations, Vadi's treatise also offers up a lengthy introduction to the principles of swordplay that help to further flesh out the framework of the teachings. While there is no proof of a direct connection between Fiore and Vadi, the similarities between the authors lead most people to lump both of them into the study of Armizare.

Die Blume des Kampfes

Die Blume des Kampfes (German for "The Flower of Battle")is a nickname given to a collection of German sources that have a considerable overlap of material with Fiore's writings, either showing that Fiore's tradition carried on into parts of Germany after his death or simply that this was the larger overall style of fencing that had already existed that Fiore was himself an initiate of. This collection of manuscripts depicts a wide array of weapons including those associated with strictly Germanic sources, such as the dueling shield. While most of the works are not accompanied with any text, von Eyb's wrestling section is very clearly detailed with explicit textual information and the beautiful illustrations of the Codex 10799 give us a very clear picture of the postures and techniques employed 200 years earlier by Fiore - making these sources very useful when studying.

Other Sources and "Frog DNA"

While these sources themselves are enough to study Armizare, sometimes it is helpful to look across the sources at other treatises that may provide useful information. One such example is trying to figure out the usage of Fiore's infamous "Posta Bicorno." Some fencers have drawn parallels between Bicorno and the "Einkhiren" position shown in some of Paulus Hector Mair's plays, which could tie such practices as winding through the Rose into Fiore's art. Apart from strictly technical information, it can also be interesting to read other sources for their views of the principles of fencing. The writings of the Bolognese School such as Antonio Manciolino's Opera Nova are interesting because they shed light on the general principles of how one should fence, the perception of fencing at the time, and various issues of practice and training (such as whether or not it is possible for an individual to learn how to use sharp swords if they only ever train with blunts). There are also occasionally parallels between the Bolognese school and Fiore's tradition, such as the virtues believed to be most important to the swordsman. For these reasons other sources are delved into, but we must be careful not to color too much of one work with another.